For decades, Wall Street has grappled with a data problem often relegated to a “black box” in the IT department. Amid an AI arms race, that black box is being forced open, and often, what’s inside is fumes – or certainly not the impeccably clean and organised datasets any ambitious firm would want.

That’s typically not IT’s fault: “Data is the exhaust from a process,” says Larry Hunt, a softly spoken 25-year data veteran who previously led major enterprise data strategy programmes at Bank of America and Wells Fargo.

“The IT team is often the scapegoat for data problems. Usually, the IT team is implementing the requirements that they got from the business. Most of the bad data that you see isn't an IT problem, it's because of a bad process.”

Data debt and data trust…

Now the Field CDO for Financial Services at data trust platform firm Ataccama, Hunt argues that the C-suite’s sudden thirst for AI-driven efficiency and innovation is colliding with decades of unaddressed data debt.

The result? A 99% experimentation rate with AI, but a dismal 3% success rate in embedding it successfully into the business, as Ataccama’s new data trust report reveals – (46% of financial services executives rank improving data quality as their top priority; a third cite it as their biggest challenge.)

The ‘Fourth Pillar’ and the efficiency mandate

This matters, because the stakes have fundamentally changed for big banks. “If you listen to the quarterly earnings reports, 10 years ago they were talking about capital ratios,” Hunt says. “Most CFOs now are talking about efficiency ratios. How much does it cost me to generate that $1 in revenue?”

This has elevated data from an IT concern to a core business imperative – what Hunt calls the “fourth pillar” of the operating model, standing alongside the well-established triad of people, process, and technology.

Yet the problem is that while most banks have built the functions of a Chief Data Office, often in response to a crisis or regulatory order, adoption of data discipline is patchwork. (Hunt is quick to emphasise that “data” as a term gets bandied about very loosely: “People say ‘data’, but they don't know exactly what they're talking about or what they're trying to explain, so you have to qualify it, right? Are you talking data analytics? Are you talking about data pipelines? Are you talking about data analysis, data models?”)

Data maturity

“There is great variability, even within organizations,” Hunt notes. “Some lines of business are going to be much better than others. There's still a lot of opportunity for most financial services companies to get there.”

This inconsistency is where the efficiency mandate breaks down.

Banks are realising they can't automate or optimise what they don't understand, and most don't truly understand their own data supply chain.

From ‘nails on a chalkboard’ to business value

The divide between the central data office and the front lines of business, where the data is actually created, has been a major source of failure.

Hunt, who ran internal "boutique consulting" teams at BofA to bridge this gap, says the approach in many data offices is often all wrong – being born as it is out of a defensive mindset and traditionally reactive efforts.

“If you show up to a consumer lending business talking about data governance, it’s going to be like nails on a chalkboard,” he says.

Instead, “talk about how governance will improve the credit card business.”

Successful data programs, Hunt argues, are often federated.

“The most successful programs understand that those frontline businesses own the data that they create,” Hunt says. “When you connect the process owner to the data they create and federate the model for what their responsibility is... that's how you drive adoption.”

It’s a pivot from a defensive, compliance-first posture to one of offense.

Anti-patterns

And the most mature firms leverage the "inception event" (often a stinging regulatory order or a bad audit) to build a holistic strategy. First, they fix the compliance issue. Then, they use that new rigor to drive efficiency.

Finally, they use that efficiency to unlock value.

For many banks, that journey is stalled at what Hunt calls the “anti-pattern” to efficiency: manual processes. He points to the consent orders that have plagued major U.S. banks, forcing them to get their data "shop in order."

The reason it’s so difficult, he says, is that most large banks are the product of decades of M&A: “They have grown over time through acquisition, and they exponentially incorporated a bunch of different federated systems.”

Often, this creates a convoluted data supply chain (from capture, to aggregation, to consumption) that is riddled with inconsistencies.

“I remember talking to the CRO at one of the companies I was at,” Hunt recounts. “His risk team spent 50% of their time translating the data from upstream. That's not their day job. Their day job is to do risk modeling.”

This "translation tax" is pure, non-value-added cost.

(“Ironically, it's quite a manual process to build an agile data architecture” as then-Citi Chief Administrative Officer Karen Peetz said in ‘22 – as the bank admitted it had some 11,000 people working on a data and digital transformation.)

"Not sustainable"

“Those thousands of people doing manual processing... it's not sustainable,” Hunt warns. “Technology has to drive the opportunity for automation.”

Yet right now an AI-frenzy means a "race to not be last" is forcing clumsy decisions. Companies are doing "lift and shift" migrations to the cloud without cleaning up their data, turning promising data lakes into "data swamps." They're struggling to deprecate legacy tech – and often the result is a C-suite demanding AI-driven insights, and data teams unable to deliver.

In his roles at major banks often “we were looking at AI cases... and it turned into, ‘We want to do all these things, but we don't have the data,’” Hunt says. “We had to reverse engineer what we could actually do, because the limiting factor wasn't the model, it was the data.”

Hunt, who now advises banks on the tooling to fix these foundational issues, cautions against looking for a silver bullet. The solution, he says, is a "pragmatic" combination of technology and a new operating model.

In his former roles, he says, the core regulatory questions “Do you know what data you have? Is it right? Where did it come from?’ were typically answered, imperfectly and expensively, with manual processes.

Software platforms have a growing role to play

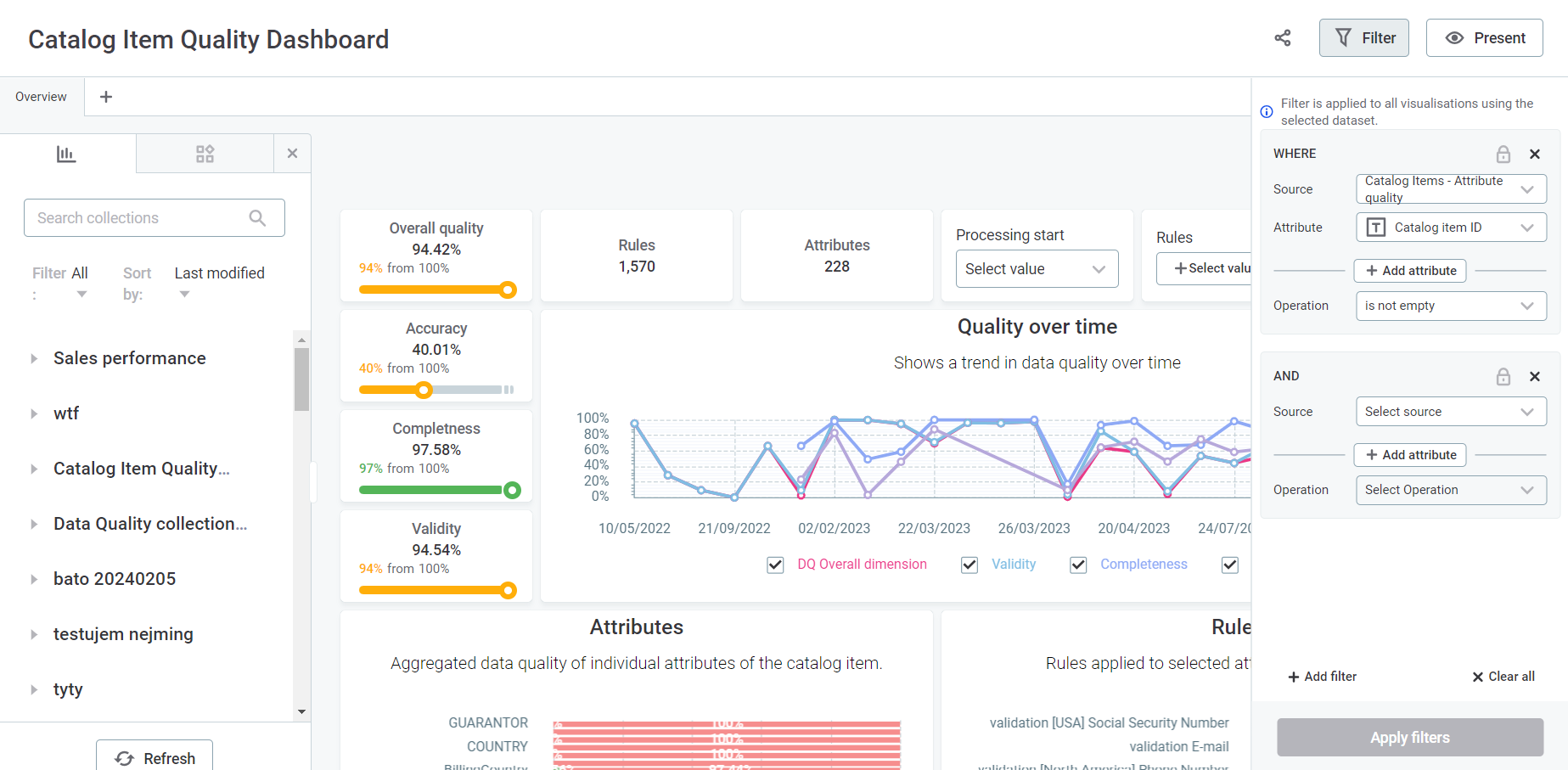

Today, unified platforms for data cataloging, quality, and lineage like Ataccama’s are designed to help automate this, providing the "Data Trust" required to begin an effective AI journey – and help compliance too.

But Hunt is quick to point out that a tool is only as good as the process around it. Necessity, however, can often be the mother of invention…

Regulatory risk is giving financial institutions the mandate and the momentum to unify data silos, establish clear lineage, and validate data in real time. Compliance, once seen as a cost centre, is now increasingly driving transformation, as institutions prepare to meet stricter transparency and accountability standards. And data trust is becoming a competitive edge.

As Hunt is keen to reiterate however: “The most successful data programs understand that those frontline businesses own the data that they create. When you connect the process owner to the data that they create and demonstrate how that delivers value, that’s how you drive adoption.”

Delivered in partnership with Ataccama.