The UK’s communications regulator is concerned that cloud customers face “material barriers” to switching cloud providers, with Ofcom saying in a report this week that it has seen growing evidence of customers already in the cloud “facing significant price increases” at contract renewal and is “most concerned about… the charging of egress fees, restrictions on interoperability and the structure of committed spend discounts.”

It says that “the hyperscalers charge… egress fees that are 5-10 times higher than some other cloud providers, such as OVHcloud and Oracle”, with over half of the respondents to its investigation citing egress fees as a concern that “is consistent across users of all the major providers, and across both those which are currently using a single cloud provider” – Ofcom says it is going to “explore this issue further ahead of our final report.”

Critics like Cloudflare have earlier claimed that AWS charges an 8000% markup on moving data off its cloud, which is, as software engineer Robert Aboukhalil puts it, “certainly an effective way to ensure that users analyze data on the same platform where they store it” -- among the observations that Ofcom also makes.

(Cloudflare spun up object storage offering R2 with no egress fees to attack this space; others like Wasabi also offer simple cloud storage pricing with no additional egress or API request charges. AWS users meanwhile highlight that although ingress traffic from the Internet is free, if traffic flows through the NAT Gateway service, there are data processing costs and “things get worse if you provision NAT gateway in different availability zone than your workload. In that scenario you end up paying Inter-AZ traffic on top of data processing price.”)

AWS and Microsoft – which dominate the UK market, with up to 70% of market share – may not yet be quivering in their boots. Ofcom is not known for its ferocity: It also investigates complaints about broadcasts and in its last reported year, of 99,562 complaints, found that just 17 reflected a breach of its rules. The two fines Ofcom levied against telecommunications providers for aggressive miss-selling meanwhile were £10,000 and £25,000; the latter higher fine being the equivalent to some 10 seconds of AWS revenue in 2022. ("I'm going to count to 10...")

Ofcom is not, of course, about to start levying miniscule fines on the hyperscalers. Instead, it is still consulting on whether to refer the cloud infrastructure market to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to carry out a market investigation and it certainly seems likely that greater focus on data egress fees is on the horizon.

Many other passages of the Ofcom report seem to lack meaningful bite, to our eyes.

A snapshot: “We note that the most cited barrier to completely switching the IaaS/PaaS provider was time and cost of making the change... Indeed, the feedback we have received from customers suggests that in some cases they may consider the reconfiguration effort as time and cost consuming rather than technically difficult” – hardly a sign of monstrous hyperscaler behaviour. Ditto Ofcom’s statement that “our evidence also indicates that customers wishing to duplicate, all or some parts of, their cloud architectures face substantial technical and financial costs associated with setting up and maintaining two parallel clouds.” (Quelle surprise.)

Ofcom’s formulation of obstacles to seamless multi-cloud as an interoperability one may seem just a touch jejune to some; it’s always been hard to just pick up a complex application and shift it elsewhere; try ERP migrations on for size, as one simple example. Containerisation and Kubernetes have also made this broader challenge easier for many for those building cloud-native applications; thanks in part to the cloud. As Patrick McFadin earlier put it to The Stack: “Kubernetes is the equaliser. It allows users to declare what they need from the parts supplied by cloud providers. It’s getting us closer to infrastructure conforming to the application and not the other way around.” (Disagree and think that a lack of cloud interoperability is a massive problem: pop an email over.)

Ofcom’s comments on concentration risk are also hardly fiery: “Should we arrive at a more concentrated market where smaller cloud providers pose a weaker constraint on the ecosystems of the market leaders, this has the potential to dampen competition and lead to worse outcomes for customers going forward…”

(“Should we arrive”? “More concentrated”? How concentrated do things need to be before we "arrive"?)

UKCloud liquidation became inevitable when AWS won the spooks

It's here at this tepid expression of concern at market concentration, that an alternative thought exercise, perhaps, particularly for public policy makers, rather begs to be explored: Whether his Majesty’s Government (HMG) itself faces a growing cloud concentration risk issue that has gone rather unremarked on.

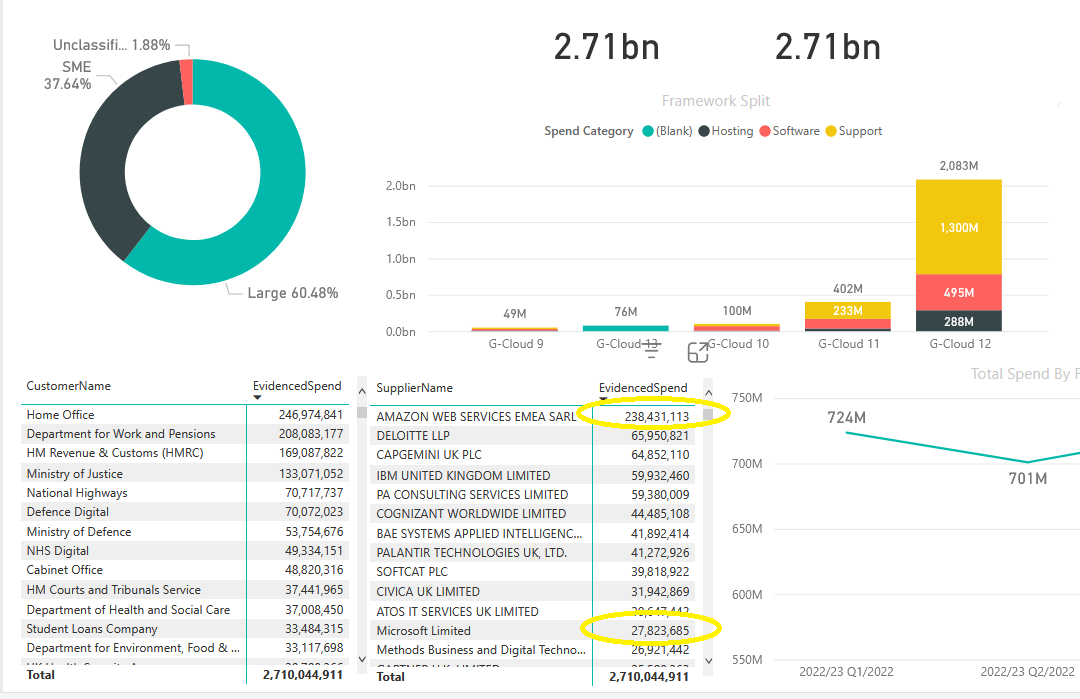

HMG itself is of course a rapidly growing hyperscale customer; and its eggs are largely and increasingly going into an Amazon-shaped basket. Over the past 36 months alone the British government has spent nearly half-a-trillion pounds on AWS services through one procurement framework (G-Cloud) alone, Crown Commercial Services data shows; far outstripping peers. Amazon has also employed numerous former senior HMG IT leaders -- all of whom are of course beyond rebuke -- and the dismal salaries on offer for many civil service IT leaders in a time of high inflation mean the revolving door into cloud-land must look hugely attractive, where and when it's offered.

As well as potential cloud concentration risk of the kind that has troubled financial services regulators (who are increasingly demanding that banks and others under their bailiwick spell out “clearly defined exit plans to allow for relocation of infrastructure, codebase, and data between cloud providers") economists would be forgiven for wondering if there is a growing risk of what one has dubbed "cognitive state capture" happening too.

It is interesting to explore the parallels with the financial services sector in the wake of 2008; also a world of intense concentration that in the wake of crisis saw then-Citigroup chief economist Willem Buiter write in the FT that “the banking establishment and the financial establishment representing the beneficial owners of the institutions exposed to the banks as unsecured creditors… have captured the key governments, their central banks, their regulators, supervisors and accounting standard setters to a degree never seen before.”

Extraordinary words. A decade later, Buiter (a Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, former Chief Economist and Special Counselor to the President of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and an original member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee) followed up in an OECD paper, claiming that “regulatory capture remains as much of an issue as it ever was. I am not only, or even mainly referring to blatant conflicts of interest created by the revolving door between regulatory and central bank appointments and lucrative positions in the financial sector, although that too remains a problem…”

Rather, he explained, “I am referring mainly to what I have called cognitive capture and what others have called cultural capture. Cognitive regulatory or state capture refers to a social-psychological, small group behaviour-based explanation of the phenomenon of “capture”. Cognitive regulatory capture (or cognitive state capture), is not achieved by special interests buying, blackmailing or bribing their way towards control of the legislature, the executive, the legislature or some important regulator or agency, like the Fed, but instead through those in charge of the relevant state entity internalising, as if by osmosis, the objectives, interests and perception of reality of the vested interest they are meant to regulate and supervise in the public interest…”

Buiter was talking about a different industry at a different time. Yet the very practical issue of a "Hotel California" cloud and the more nebulous one of cognitive state capture in our view deserves more exploring. (After all, debate is rife about the efficiency of cloud: “Across 50 of the top public software companies currently utilizing cloud infrastructure, an estimated $100B of market value is being lost among them due to cloud impact on margins relative to running the infrastructure themselves” VC firm Andreessen Horowitz estimated in 2021.)

The “perception of reality of” an AWS or Microsoft are, of course, that customers came to it willingly, can leave when they want (at a cost) and that its impressive innovations being a draw for the public sector are hardly a crime. Yet the extent of a growing reliance on their services for an ever deeper swathe of critical public services may deserve more scrutiny and conversation than they receive. We would welcome our readers' views...